Design Patents

Sneakers and Fancy Dresses Provide Guidance on Written Description Requirements for Design Patents

In last month’s column, we looked at recent design IPR decisions that focused on anticipation and obviousness arguments. In this column, we will consider recent cases that touch on the application of 35 U.S.C. § 112 to design patents.

In February 2014, and again in April 2016, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) issued proposed guidelines for the application of § 112 to design patents. In the later set of guidelines, the USPTO asked for examples to illustrate proposed approaches to application of the proposed guidelines. Each time, the design patent bar provided comments to the USPTO. In some comments, the bar noted that the law regarding written description had not changed and thus there was no need for new guidelines. Moreover, in the bar’s view, any examples should come from litigation or appeals to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), rather than hypothetical ones.

While we are not aware of recent ex parte appeals to the PTAB or the Federal Circuit that might include such examples, some recent post-grant cases at the PTAB that could provide some insight on this issue.

Section 112 is typically considered in a number of contexts for design patents. Two are relevant here. First, when an applicant files an application that claims priority to a prior application, the examiner may reject the claim of priority on the grounds that differences or changes in the later application are not supported by the former application. Second, during prosecution, when an applicant attempts to amend the application, the examiner may reject the change as being directed to “new matter”—meaning not being supported by the original disclosure. The two post-grant matters discussed below illustrate these situations.

Skechers USA, Inc. v. Nike, Inc., IPR2016-00870

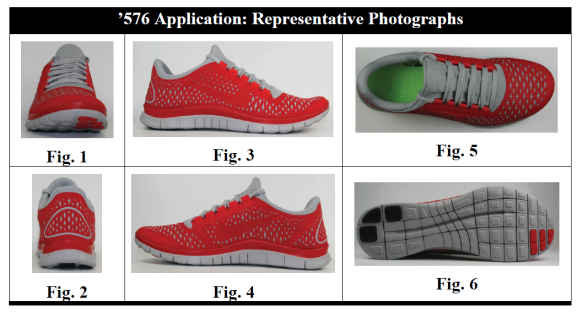

Skechers filed a series of petitions against Nike involving design patents directed to athletic shoes. In IPR2016-00870, like the other petitions, Nike had filed a series of design patent applications claiming priority to single application, in this case, Application No. 29/414,576:

Figs 1-6 (of 69 total color images in ’576 application)

Over the next couple of years, Nike filed a series of continuation applications claiming priority to the ’576 application, culminating with the D725,356 patent, the subject of this IPR.

Unlike the original ’576 application, the ’356 patent did not claim priority to the entire shoe design, but rather only to the bottom sides and sole of the shoe.

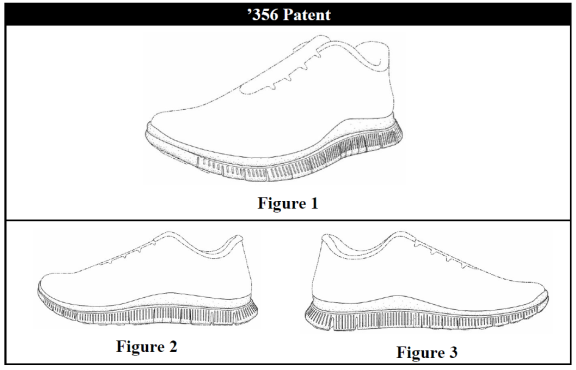

Figs 1-3, ’356 patent

Figs 1-3, ’356 patent

Petitioner Skechers charged that this claim of priority did not meet § 112, because it disclosed seven features not present in the priority application. As such, according to Skechers, the ’356 patent should only be entitled to its actual filing date, not the filing date of the ’576 application. As a result, in Skechers’ view, the ’356 patent was not valid because it was anticipated by Nike’s own European filing directed to this same design registered two years prior to the filing of the ’356 patent.

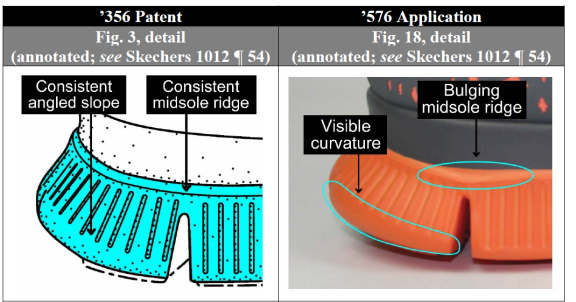

To support its point, Skechers engaged in a detailed comparison of the disclosure in the ’356 patent and the ’576 application, often relying on enlarged views of the two disclosures with extensive annotations:

In its preliminary response, patent owner Nike first challenged Skechers’ backdoor attempt to challenge § 112 and priority in an IPR. Nike noted that during prosecution it asked for, and received, a determination from the examiner confirming its claim of priority back to the ’576 application, and urged the PTO not to revisit this issue. Nike also noted that the examiner was aware of the contemporaneous Nike European registration. On the merits, Nike asserted that Skechers had not considered the two disclosures “as a whole” but rather that Skechers had “selectively reli[ed] on inaccurate and misleading illustrations” and engaged in improper “microanalysis.”1 On the contrary, Nike urged the Board to recognize that the design of the ’356 patent was disclosed in the ’576 application and that the portions of the ’356 patent were not arbitrary, but rather had basis in the parent application. In arguing it case, Nike relied on Federal Circuit case law, including Racing Strollers, Inc. v. TRI Industries, Inc., 878 F.2d 1418 (Fed. Cir. 1989) and In re Daniels, 144 F.3d. 1452 (Fed. Cir. 1998), Board decisions, and the PTO’s written description guidelines released in April 2016, discussed above.

The Board denied institution.2 In its decision, the Board initially noted that the examiner considered Nike’s priority claim and “had an evidentiary and factual basis” for his determination regarding the priority claim. Moreover, the Board was not “persuaded by Skechers’ comparative micro-analysis of the drawings in the ’356 patent and the photographs of the ’576 application, e.g., comparisons detailing minor drawing inconsistencies, slight shading variations, and use of broken lines to indicate unclaimed subject matter, that ‘Nike has claimed an entirely new design in the ’356 Patent[.]’”3 By using enlarged images of parts of the design, the Board found Skechers’ comparisons to be “excessively critical micro-analysis that any observer, when comparing the photograph to the respective line drawing, would be hard-pressed to discern.”4 Moreover, citing to In re Daniels, the Board found the drawings in a continuation need not be “exactly the same as the photographs of the parent.”5 and where, as here, the drawings are sufficiently consistent with the photographs, the Board determined that the inventor had possession of the claimed design in the ’356 patent at the time of the filing of the parent application.6

Finally, the Board also distinguished the present case from the Board’s Decision in Munchkin, Inc. v. Luv N’ Care Ltd.,7 in which the Board found that the parent utility patent did not support the priority claim to the later-filed design patent. First, the Board noted that, in Munchkin, a side-by-side comparison was made “without any embellishment or magnification of the drawings” and that based on that comparison, the Board found that two key features of the spout design in the originally-filed drawings were substantially different in relative size, shape, and structure from the claimed design.

David’s Bridal, Inc. v. Jenny Yoo Collections, Inc., PGR2016-00041

Filed on September 8, 2016, the petitioner, David’s Bridal, argues that the ’723 patent is invalid as indefinite under § 112, as well as anticipated under § 102 and obvious under § 103.8 The ’723 patent was filed as a divisional application to a prior application, which included disclosure directed to both a long and short version of a dress.9

In the prior application, the examiner issued a restriction requirement between two embodiments, noting that the long version of the dress appeared to be missing sufficient views and was thus “nonenabling.”10 The applicant elected to proceed with the short version of the dress and later filed a divisional application (which issues as the ’723 patent) directed to the long version. When the applicant filed the divisional application, the applicant added three figures:

|

|

|

Figures Added to D744723

David’s Bridal contends that these three figures were new matter, and thus the ’723 patent should not be afforded the earlier priority date of the parent application. As a result, David’s Bridal argues that the ’723 patent is eligible for PGR review and further, is invalid in view of the patent owner’s own intervening public disclosure of the long dress design.

A Preliminary Patent Owner Response is due by early December and the Board should issue its Institution Decision in March 2017. It will be interesting to see how the Board treats the issue of eligibility for PGR review and the introduction of additional figures.

Lessons Learned

As with previous post-grant cases, these cases have or will provide helpful insights for prosecution of design patents in the future. As with the Munchkin IPR, these cases will serve as examples of the application of § 112 to design patents. In addition, the Board seems to have credited the examiner’s determination during prosecution that Nike’s child application should be afforded the priority date of the parent, suggesting that this may be a helpful strategy. Likewise, the David’s Bridal case will offer important insight into the effect on a priority claim by adding figures to the later-filed application. Those engaged in design patent prosecution will likely find following the PTAB post-grant design cases helpful.

1 Nike Preliminary Patent Owner Response, IPR2016-00870, Paper 7 at 3.

2 Institution Decision, IPR2016-00870, Paper 6 at 3.

3 Id. at 9.

4 Id. at 14.

5 Id. at 20 (emphasis in original).

6 Id. at 21.

7 IPR2013-00072 (PTAB April 21, 2014).

8 David’s Bridal, Inc. v. Jenny Yoo Collections, Inc., PGR2016-00041, filed Sept. 8, 2016.

9 The ’723 patent claims priority to an application that was filed before the AIA was enacted. Thus, this application would not appear to qualify for PGR review. However, the petitioner argues that this priority claim is not valid, and thus the ’723 patent should be treated as being filed on August 10, 2013, and thus qualified for PGR review.

10 PGR2016-00041, Paper 1 at 7.