Design Patents

Selling Globally? Protect Locally – Strategic Planning for Design Rights Worldwide

In today’s worldwide marketplace, many companies hope to sell their products abroad. And many companies will certainly consider having their products manufactured in another country. So in this month’s column, I’m going to take a closer look at the decision to file design patents (or design registrations as they are called in many parts of the world) outside your home nation. Many of these considerations will sound familiar to filers of utility patents across multiple jurisdictions, but the details are very different.

Design Protection Systems

Initially, it is important to understand that there are actually three broad types of systems for protecting design rights: (1) registration systems; (2) examination systems; and (3) hybrid systems.

Registration Systems. In registration systems, typically the application is briefly reviewed for completeness (the application states it has five figures and five figures have been filed). Also, the figures are considered to determine if they all depict an article of the same class—meaning figures of a lamp are not mixed with figures of a coffee pot. China, Mexico, South Africa, Switzerland, and the European Union (through its Office for the Harmonization in the Internal Market (OHIM)) are all considered registration systems. Registration systems are usually quicker and have lower costs.

Examination Systems. In examination systems, design applications are reviewed for compliance with procedural matters (as in registration systems) as well as for novelty, obviousness, originality, and consistency between the figures, depending on local laws. In most examination systems, an examiner conducts a search for prior art and compares the results to the design shown in the application. The United States, Japan, India, and Taiwan have examination systems. In examination systems, typically it takes longer for the patent to issue than in registration systems, and the fees can be higher. Some examination systems (such as in the United States) offer an expedited examination process for an additional fee.

Hybrid Systems. Some countries have adopted systems that fall in between the registration and examination systems. For example, in Australia and Brazil, designs follow a registration process, but there is also an optional follow-on examination process required before a design can be enforced. This allows applicants to register a large number of designs (at a lower cost than with examination) and decide later which registrations to take through the examination process. The date of priority for prior art is the date when the registration was filed. Other countries, such as South Korea, have a nonsubstantive examination process for certain “short lifecycle” classes, such as food products, clothing and accessories, printed materials, computers, and screen icons. But South Korea requires substantive examinations for other classes such as household items and furnishings.

Timing of Filing

For utility patents, practitioners tend to think in twelve-month periods, because most foreign filings must be made within one year of the priority filing. For designs, this twelve-month period is shortened to six months. So, the decisions for foreign filing must be made in half the time. As a result, it is a good idea to think about this issue before you find the six-month deadline looming.

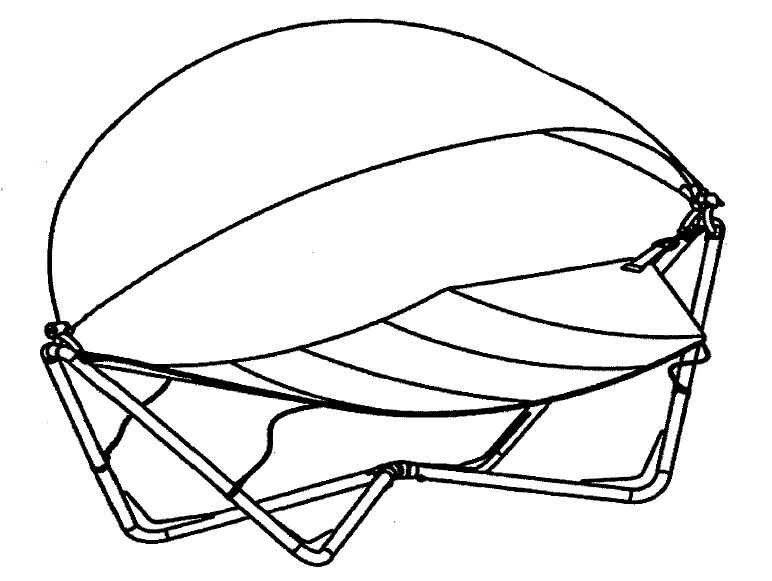

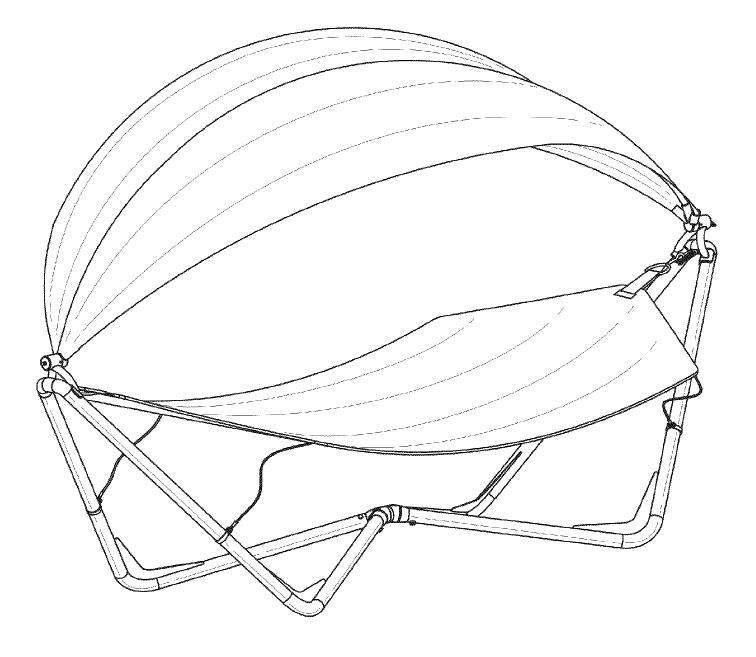

|

|

|

Original Priority Filing CN 2012 3 0297809 |

U.S. Patent No. D706,054 - Swing Bed with Canopy |

Another difference is that design filings are typically made after the design is finalized, which is often shortly before the public announcement or first sale of the new product. So thinking about your strategy ahead of time is important, because your decision makers (and designers) will likely have many other things to worry about during this busy period.

Choosing Where to File for Protection

The biggest question is usually where to file. Of course, your final decisions will be dictated by business realities and budget constraints, but it is important to think broadly at first to build your prioritized list of countries. Some important considerations include:

- Where do you plan to sell the product? First and foremost, you will want protection from your competitors and any potential counterfeiters in the markets where you plan to sell the design. Rank the markets by potential sales from most to least.

- Where did you invent the design? Often, most of sales will be in your own backyard. But if you choose not to file in your home country, then you may need to consider foreign filing licenses, depending on your local laws.

- Where will you make the product? Many have heard of suppliers making “extra” runs of a product afterhours or continuing to sell an older design to other retailers after you’ve moved on. Getting design rights in the countries where your suppliers operate combats this threat.

- Where will your competitors make their product? Even if your company chooses to make your product locally, it is important to consider that your competitor may have the product made overseas. As noted below, one of the best enforcement tools can be to have any infringing designs stopped at the border of the exporting country before they ever get put on a ship.

Of course, these are just some of the questions. Other important issues include filing in places that will have a large impact (such as filing at OHIM and getting protection in all the European Union countries at once) and in places with a large customer base. The courts of some countries have greater or lesser respect for design rights and that is reflected in the damages amounts and the ease of getting injunctive relief. Japan, Switzerland, and OHIM will permit infringing designs to be stopped at the border, and in the case of a change in EU law, in some cases, the infringing product can be destroyed by Customs officials.

Don’t Forget the Differences in Design Law

Prior Public Disclosure or Sale. Another important consideration is whether you’ve disclosed the design before filing. Some countries require “absolute novelty” for design registrations, while others have grace periods. Some grace periods, like for the OHIM, are more generous than in places like the United States, which recently limited its grace period; the exact bounds of the U.S. grace period are still to be determined. Other countries will permit certain types of limited disclosure in connection with government or university activities.

Publication of Design. Smart companies file for design rights before public disclosure, but may still wish to keep the design secret for a bit longer after filing. In countries like the United States, designs are kept secret until they issue (typically fifteen to eighteen months after filing). But in other places, like OHIM, the design will be registered almost immediately and become publicly available shortly thereafter. Therefore, it is important to consider if you would like to defer registration (possible in OHIM) or ask that the design right be kept secret (possible in South Korea under certain circumstances).

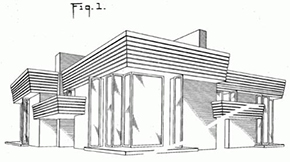

|

|

U.S. Patent No. D114,204 to Frank Lloyd Wright - Dwelling |

Preparing the Application

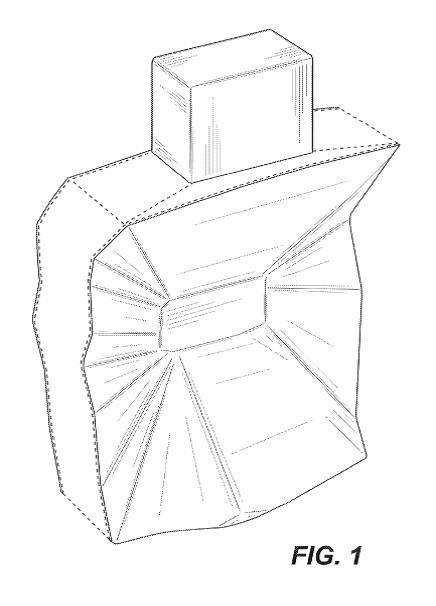

In preparing your priority application for filing, it is helpful to make decisions that will make your foreign filing easier and less expensive. Some places will permit you to file computer-generated graphics (such as OHIM), which can be easily created from most CAD or e-drawing programs, but these graphics may present issues when filing elsewhere. The United States Patent and Trademark Office, for instance, strongly prefers line drawings. This is usually in the interest of the applicant as well, because line drawings permit the applicant to disclaim the unimportant details of the design. Commissioning line drawings is an additional expense, but usually any changes that need to be made for the different jurisdictions can be made quickly and at little additional cost.

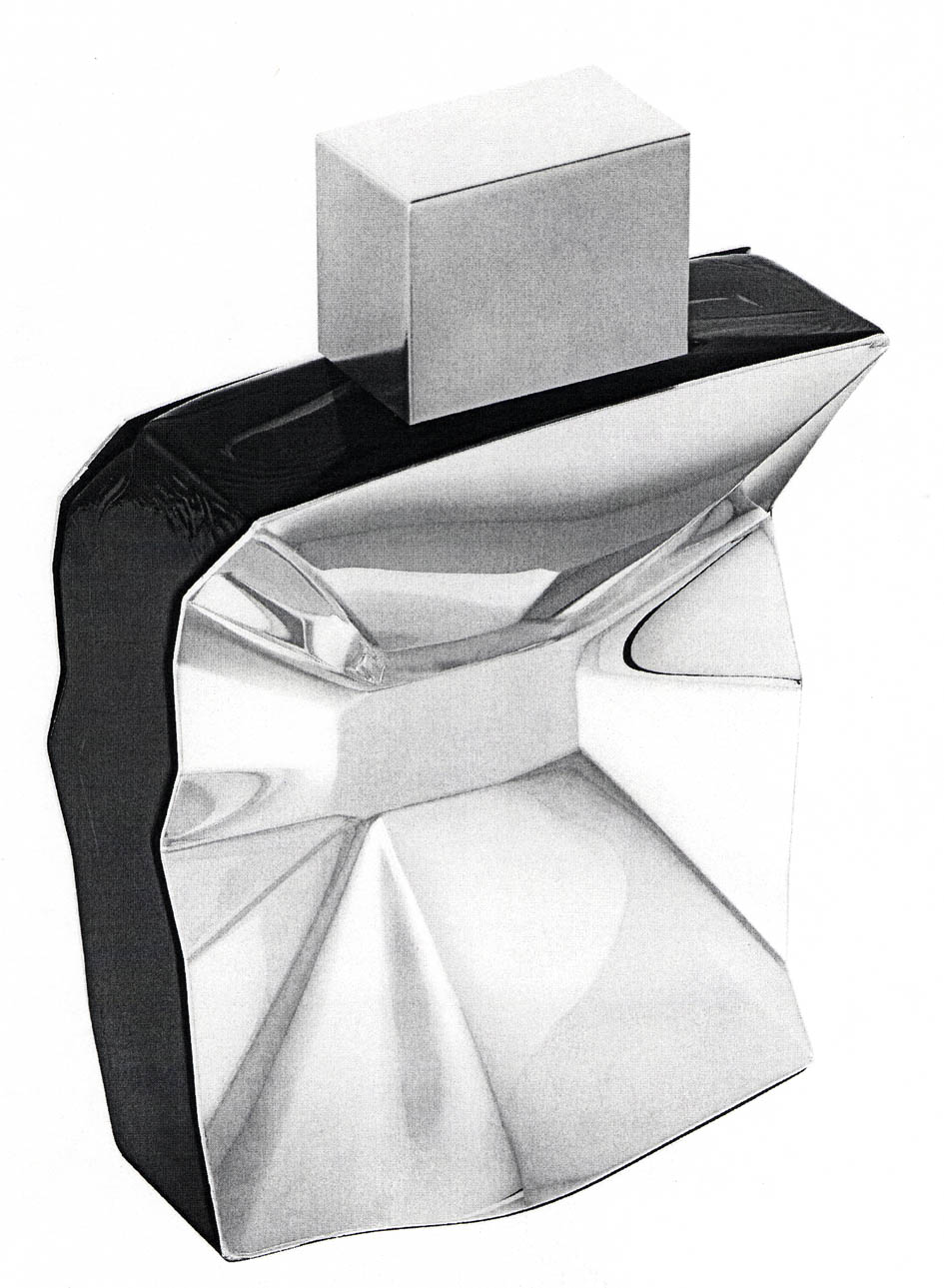

|

|

|

Original Priority Filing CN 2012 3 0297809 |

US Patent No. D675529 - Container for a Fragrance |

| Comparison of OHIM and US Design Filings | |

It is also important to think about the types of disclosure (meaning what views—top, bottom, right, left, etc.) you plan to include in your application. For instance, OHIM limits a single design to seven views. On the other hand, the United States has no limit, but requires that there be “sufficient views” to completely show the design. Some countries encourage multiple views from different perspectives (e.g., a top, front, right perspective view and a bottom, rear, left perspective view) over more elevation (i.e., “straight on”) views. Other countries will permit a limited number of perspective views in addition to the six traditional elevation views. In other words, it is important to think ahead to make sure that all of these masters can be served and that your priority application will support all later applications.

Using the Hague System for International Registration

In the United States, there has been much discussion about the Hague System for International Design Registration. There are currently sixty-two members of the Hague Agreement, including OHIM, the African Intellectual Property Organization, and as of July 2014, South Korea. The United States is expected to complete the Hague process in the first half of 2015 and begin accepting applications shortly thereafter. Notably, China, Japan, Australia, Brazil, and Canada are not currently members.

Simply put, the Hague System allows a single point of deposit for design applications that may be destined for any other member country. For Hague filers, there will be one electronic filing system and all fees can be paid in a single currency at the same time. (The fees, however, will not be lower and the accepting country’s office will charge a fee for sending the applications to the other countries.)

But the Hague System will not necessarily simplify the overall process. The local laws of each country still govern registration—including local drawing rules and disclosure requirements of known prior art (such as in the United States). And all objections or rejections to applications must be dealt with directly at the national offices. In some cases (such as in theUnited States), this requires that the applicant retain a local representative who is admitted to deal with that country’s office. Generally, it will be important to consult foreign local counsel before filing your application through the Hague System.

Retaining Skilled Local Counsel

The above discussion has hopefully convinced you that it is paramount to rely on skilled local counsel in each jurisdiction. Local counsel can be invaluable for providing prefiling advice to get applications through registration or examination more quickly and for interpreting the local examiner’s idiosyncrasies. Finally, as design and design rights gain recognition throughout the world, many countries are reforming their local laws and competent local counsel can keep you informed about any changes.