January 2013

Board’s Obviousness and Nonobviousness Determinations Affirmed for Claims to Cartons for Dispensing Cans

| Judges: Prost (dissenting-in-part), Moore, Wallach (author) |

| [Appealed from Board] |

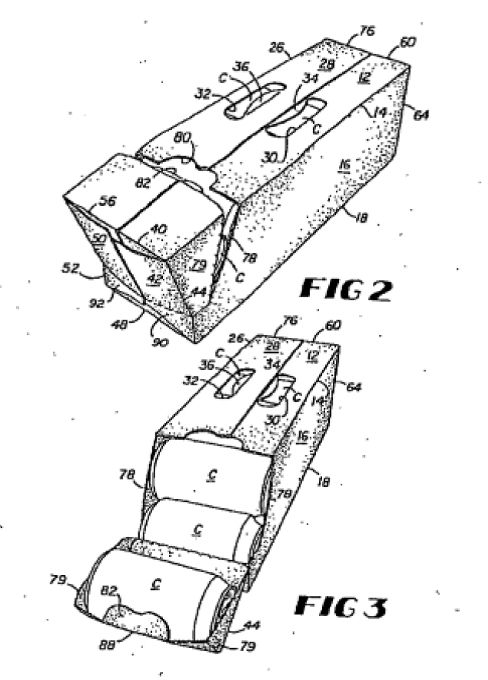

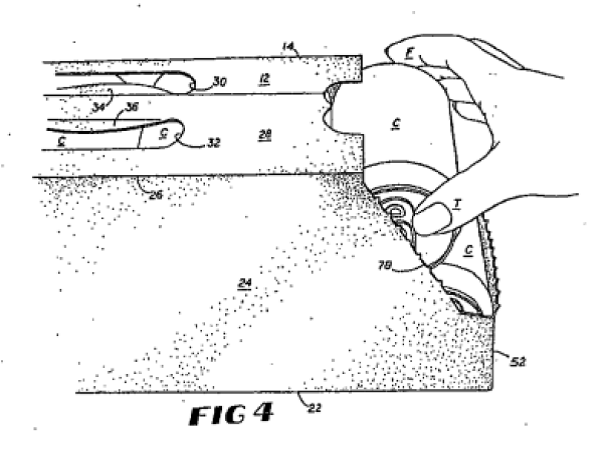

In C.W. Zumbiel Co. v. Kappos, Nos. 11-1332, -1333 (Fed. Cir. Dec. 27, 2012), the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s obviousness and nonobviousness determinations in the inter partes reexamination of U.S. Patent No. 6,715,639 (“the ’639 patent”). The ’639 patent is assigned to Graphic Packaging International, Inc. (“Graphic”) and is directed to a carton or box that holds containers such as cans or bottles. The claimed carton has a dispenser-piece that has a finger-flap on top for pulling the dispenser-piece into an open position or fully off the carton. In one embodiment, the finger-flap is located between the first and second containers in the top row of the carton.

Slip op. at 4.

Upon request for inter partes reexamination by C.W. Zumbiel Co., Inc. (“Zumbiel”), the Examiner rejected certain claims of the ’639 patent as obvious and confirmed the patentability of others. The Board affirmed, concluding that claims 1, 3-8, 10-13, and 19-21 were obvious and unpatentable over U.S. Patent No. 3,178,242 (“Ellis”) in view of German Gebrauchsmuster No. G85 14718.4 (“German ’718”); that claims 1, 3-8, and 10-12 were obvious over Ellis in view of German ’718 and U.S. Patent No. 2,718,301 (“Palmer”); and that claims 2, 9, 14, and 32-39 were not obvious and therefore patentable. Both sides appealed.

Regarding Graphic’s cross-appeal, the Federal Circuit looked to representative independent claims 1 and 13, and held they were obvious. First, the Court addressed the “finger-flap” limitation and whether Ellis in view of German ’718 taught the location for the finger-flap as the top panel of a carton. Graphic argued that it did not, because the Ellis carton is laid on its side to open while German ’718 is opened from the top. The Court disagreed, holding that the Board correctly concluded that “providing the finger opening on the top wall of the carton would be a predictable variation [of the carton in Ellis] that enhances user convenience, as evidenced by German ’718, and is within the skill of a person of ordinary skill in the art.” Id. at 15 (citation omitted).

“The point here is not that the Board got the facts wrong. The point is that contrary to the Supreme Court’s instructions, an ‘overemphasis on the importance of [teachings of prior art]’ has insulated the Board’s analysis from pragmatic and common sense considerations that are so essential to the obviousness inquiry.” Prost Dissent at 5 (alteration in original) (quoting KSR Int'l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 419 (2007)).

Second, the Court addressed the “fold-line” limitation, rejecting Graphic’s argument that using the German ’718 fold line to form the dispenser in Ellis would not have been obvious. Graphic contended that because the fold line in German ’718 was used to keep the cover attached to the carton and thus was not a tear line, its teachings were inapplicable to Ellis. The Court disagreed, holding that substantial evidence indicated that Ellis in view of German ’718 taught a perforated line for both tearing and folding.

Third, the Court addressed the “free-ends” and “single tear-line” limitations of claim 13. Graphic challenged the Board’s construction of the terms and argued that the tear line in Ellis did not extend to the “free ends” and was interrupted by a cut-out handle, and thus did not teach a single tear line. The Court held that the end of a flap is the edge, and the tear line did extend in a single line to the edge of the carton. Because the end was removed in one piece, there was a single tear line. The Court thus affirmed the Board’s decision that certain claims of the ’639 patent were obvious.

Turning to Zumbiel’s appeal, the Federal Circuit looked to representative dependent claim 2 and held it was not obvious. First, the Court addressed the “finger-flap” limitation and whether the recited location of the finger-flap between the first and second cans was obvious. “Zumbiel argue[d] that the Examiner and Board, by finding independent claims 1, 8, and 13 obvious but not dependent claims 2, 9, and 14, ‘def[y] both logic and common sense.’” Id. at 20 (second alteration in original) (citation omitted). The Court stated that Zumbiel’s contention hinged particularly on the Board’s decision that Palmer “only suggests where to provide a handle on a carton, not where to initiate a container opening.” Id. at 20-21 (citation omitted). Zumbiel argued that “both Palmer and the ’639 patent provide a way for the user to insert their fingers into the carton and whether this occurs ‘for the purpose of carrying the carton or for opening the carton’ is ‘of no moment.’” Id. at 21 (citation omitted). The Court disagreed, holding that substantial evidence supported the Board’s finding that Palmer provides little information on where to place the finger-flaps. “Palmer concerns a carton with a finger flap, the purpose of which is to provide a grip for transporting the carton, a separate feature found in the ’639 patent unrelated to the finger-flap located between the first and second containers used to initiate tearing.”

The Court also held that substantial evidence supported the Board’s finding that the location of Ellis’s tear line would not place the finger-flap near the location of the first and second containers on the top row, as recited in claim 2. Additionally, the Court found that Ellis teaches away, as it specifies “a distance more than one-half diameter and less than one diameter of one can.” Id. at 22 (citation omitted).

Next, the Court addressed Zumbiel’s argument that the Board erred in considering the claim preamble when determining patentability. According to Zumbiel, because the term “containers” was recited in the preamble, it could not be a claimed limitation of the invention. The Court disagreed and held that because “containers” as recited in the claim body depended on the preamble’s “plurality of containers” as an antecedent basis, the terms recited in the preamble were claim limitations. The Court thus upheld the Board’s conclusion that certain claims of the ’639 patent were nonobvious.

Judge Prost dissented-in-part, agreeing that claims 1 and 13 were obvious but disagreeing with respect to claim 2. Judge Prost believed that “a common sense application of the obviousness doctrine should filter out low quality patents such as this one,” and stated that she could not join the majority in “endorsing the Board’s incorrect approach.” Prost Dissent at 1-2. According to Judge Prost, “[t]he claimed invention takes the opening from Ellis, takes the stacked can configuration from another box, and puts them together” to get “as one would expect—a box that has the known benefits of Ellis’s opening and the known benefits of a stacked can configuration.” Id. at 3. Regarding the “proper positioning of the tear line,” Judge Prost opined that the four other options for location were either “offensive to common sense” or would make for “awkward” designs. Id. at 3-4. “More importantly, however, whether some of the alternatives would work just as well or not, the patentee’s choice of tear-line-placement involves no more than the exercise of common sense in selecting one out of a finite—indeed very small—number of options.” Id. at 4. “The Board’s approach relegates one of ordinary skill to an automaton” by overemphasizing the teachings of the prior art while ignoring “pragmatic and common sense considerations that are so essential to the obviousness inquiry.” Id. at 5.

*Forrest A. Jones is a Law Clerk at Finnegan.