Summer 2012 Issue

Civil Cases

Gucci Am., Inc. v. Guess? Inc.,

2012 WL 1847646 (S.D.N.Y. May 21, 2012)

CASE SUMMARY

FACTS

Plaintiff Gucci America, Inc. (“Gucci”) and its affiliated companies own and control the world famous GUCCI brand. Among Gucci’s iconic designs are its Green-Red-Green stripe design (“GRG Stripe”), its “Stylized G” design mark, and its “Diamond Motif” trade dress, featuring a repeating diamond pattern bearing interlocking paired G letters on the corners. Gucci has used these iconic designs for decades on a wide variety of products, ranging from handbags to sunglasses, watches, and car interiors.

Defendant Guess? Inc. (“Guess”) sells branded apparel and accessories in hundreds of retail stores and over one thousand department stores nationwide. Since its founding in 1981, Guess has established itself as a “mid-market lifestyle brand” for men and women. Guess has promoted its brand name in a script-font with a “loop” in the letter “G” at the beginning of the GUESS name and/or an underline under the GUESS name (“Guess Script”) on its products since the early 1980s. Guess first sold products bearing a “Square G” design in 1996, and has used the Square G design on over fifty different styles of handbags, selling millions of units of merchandise bearing that design.

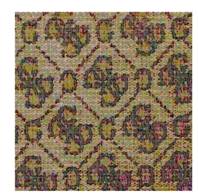

By its own admission, Guess began referencing Gucci designs for its products in the early 2000s. In 2003, Guess designed its “Quattro G” pattern, featuring a diamond design “anchored” in its corners by a “Quattro G” design. After the “Quattro G” handbag was released in 2005, Guess licensee Marc Fisher Footwear sent its Italian fabric agent clippings of Gucci fabric to create a two-tone woven canvas look and brown-beige color scheme. Handbags bearing the “Quattro G” design in this two-tone canvas design became a hit, and Guess used the design on various styles of handbags and shoes for several seasons.

In 2007, Guess designers came up with a “Melrose 2 men’s shoe” design, which, as one designer instructed the shoe manufacturer, should bear striping detail that is “Green/Red/Green like . . . GUCCI.” Guess designers further instructed the shoe manufacturer to “please reference the GUCCI sneaker” for the correct stripe color for the Melrose 2 shoe. In November 2008, however, a Guess attorney sent an e-mail to the manufacturer with instructions to “stop using Gucci red and green ribbon detail” on the shoes, and ordered that the shoes be withdrawn from Guess’s website and stores.

That same month, Gucci first learned of the Melrose 2 shoe when an investigator for Gucci purchased a Guess men’s shoe bearing the GRG Stripe. Despite Guess’s recall instructions, Guess shoes bearing the copycat GRG Stripe were still produced.

Gucci filed suit against Guess and a number of Guess licensees in May 2009. In its complaint, Gucci alleged trademark infringement and counterfeiting of iconic Gucci designs “in an attempt to ‘Gucci-fy’ [Guess’s] product line.”ANALYSIS

Following a bench trial, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York found in favor of Gucci on most of its trademark-infringement claims.

Regarding Gucci’s claim that Guess’s Quattro G pattern infringed its Diamond Motif trade dress, the court found that Gucci’s Diamond Motif was entitled to protection, despite the fact that it was unregistered. Applying the test for likelihood of confusion, the court found that while the strength of the Diamond Motif mark weighed in favor of Gucci, the similarity of the marks weighed only slightly in favor of Gucci. The court noted the similar elements in the two patterns, including the obvious use of the letter “G,” but also recognized that there were differences, such as Guess’s use of its Quattro G design to “anchor” the corners of the diamond design. Gucci’s diamond design did not feature any Gucci marks in the corners of its Diamond Motif. The court did find, however, marked similarities between Gucci’s Diamond Motif and Guess’s Quattro G design when the Guess design appeared “in brown/beige colorways on a two-tone canvas background.” A side-by-side comparison below shows Gucci’s Diamond Motif (left) and Guess’s Quattro G pattern (right).

Ultimately, the court concluded that a likelihood of confusion existed between Gucci’s Diamond Motif trade dress and Guess’s Quattro G pattern, but only for Guess’s products bearing the Quattro G pattern in “brown/beige colorways.” Accordingly, it limited Gucci’s damages for the infringement of the Diamond Motive trade dress to Guess’s profits on the sale of those brown/beige products only.

The court next concluded that Guess’s use of Gucci’s iconic GRG Stripe on a shoe constituted trademark infringement, noting that Guess’s conduct was “so egregious” that a full likelihood-of-confusion analysis was unnecessary. The court concluded as a matter of law, however, that Guess’s use of alternative color combinations “visually dissimilar” from Gucci’s GRG Stripe did not create a likelihood of confusion. Accordingly, the court limited Gucci’s damages to profits from the sale of products bearing the green-red-green stripe. A side-by-side comparison of Gucci’s GRG Stripe shoe (left) and Guess’s GRG Stripe shoe in a brown-red-brown color scheme (right) is shown below.

Analyzing Guess’s Square G design, used since Guess’s founding in the early 1980s, the court found only three instances of use of the mark that were likely to cause confusion with Gucci’s Stylized G. Noting that Gucci had used its Stylized G primarily to line the inside of its handbags and that it was a relatively weak mark, the court found that Guess’s mark generally did not cause a likelihood of confusion. After “exhaustively reviewing” Guess products bearing a Square G design, the court found that only three products—a belt and two shoe styles—bore the Square G design in a manner “substantially identical in shape] that . . . will convey the same overall commercial impression as the Stylized G.” The Square G design-infringement finding was thus limited to these items.

In addition, the court held that the Guess Script did not infringe the Script GUCCI mark, based in part on the fact that “the use of script fonts is extremely common in the fashion industry.” The court noted the dissimilarity between the Guess Script and Script GUCCI mark, stating that the Guess Script “creates a distinct commercial impression in line with the ‘Guess Girl’ aesthetic.” The court found no likelihood of confusion “whatsoever” based on its analysis of the remaining likelihood-of-confusion factors.

Regarding Gucci’s dilution claims, the court found that Guess’s Quattro G and GRG Stripe marks created a likelihood of dilution. The court determined that both designs were specifically created by Guess to trade off the goodwill associated with Gucci’s iconic Diamond Motif and GRG Stripe designs. Similar to its infringement ruling, the court limited its finding on dilution of the Quattro G pattern to instances in which that pattern appeared in a brown and beige diamond motif, and limited its finding on dilution of the GRG Stripe design to green-red-green stripe combinations only.

The court granted Gucci’s claim for cancellation of Guess’s trademark registration for its Quattro G pattern, finding that Guess had not used the pattern in a square orientation, as depicted in its registration. The court found that Guess’s use of the Quattro G pattern in a diamond orientation created a “distinct commercial impression” from its use in a square orientation, and concluded that Guess had abandoned its mark shown in the Quattro G pattern registration.

The court denied Gucci’s counterfeiting claims, stating that counterfeiting claims are reserved for “those situations where entire products have been copied stitch-for-stitch.” The court noted that Gucci’s counterfeiting claims were “more appropriately addressed under traditional infringement principles.”

The court found that the defendant was not entitled to any of its equitable defenses, namely, laches, acquiesence, and equitable estoppel, and that Gucci had not abandoned any of its trademarks. Also, the court concluded that Gucci’s claims regarding the Diamond Motif trade dress were not barred by the doctrine of aesthetic functionality, noting that Gucci was not claiming trade-dress rights in canvas fabrics in brown/beige colorways, but was instead “claiming trade dress rights in such fabrics in combination with the use of the Repeating GG pattern.”

Finally, with regard to damages, the court denied Gucci’s request for actual damages because its calculation was too “speculative,” as calculated by Gucci’s expert. Although Gucci’s expert alleged that Guess had made more than $200 million in profits for goods bearing the accused designs, the court found that Gucci was only entitled to Guess’s net profits from those products found to infringe, namely, products bearing the GRG Stripe design in green-red-green combinations and products bearing the Quattro G pattern in a brown-and-beige motif. The court concluded, after weighing all the equities, including the need to deter future willful infringement, that Gucci was entitled to $4,613,478 of Guess’s profits.

The court permanently enjoined Guess and its licensees from using the Quattro G pattern, GRG Stripe, and certain Square G marks, stating that “the conclusions of infringement and dilution give rise to a presumption that Gucci has suffered irreparable harm in that it has lost goodwill towards its unique brand as well as the ability to control its reputation in the marketplace.” The court noted that such injuries could not be remedied fully by a monetary award.

Notably, the judge expressed her distaste for the nature of the three-year litigation between the parties, and stated her hope that future disputes between fashion companies “will be limited to the runway and shopping floor, rather than spilling over into the courts.”

CONCLUSION

Even in the face of strong evidence of the intentional copying of a famous design, a court may limit damages for trademark infringement and dilution to a defendant’s profits from the sale of products that featured the infringing design in a particular color or as part of a particular pattern.