Design Patents

Lessons Learned from Recent IPR Decisions Involving Design Patents

Crafting an argument for a design patent office action response can feel like a trip back in time. The Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) regularly relies on court decisions from well into the last century1 and the one before.2 The MPEP also frequently cites Board decisions that are quite long in the tooth.3

Compounding matters, design patent applications are infrequently appealed, compared to their utility patent application cousins, leading to less guidance from the Board.4 For example, at the end of FY2016, only 63 ex parte appeals were pending in design cases, compared to 16,438 total ex parte appeals pending. That’s 0.3% of the total appeals—significantly less than the representation of design patents in patent space as a whole.5 In FY2016, the Board only issued sixteen total decisions on ex parte appeals, seven affirmances of the rejection, and nine reversals—and likely only the nine reversals may ever become publicly available.6 Appeal decisions available to the public from design cases are generally those that reverse the decision of the examiner, where the application eventually issued as a patent.7

As a result, design patent inter partes review (IPR) decisions offer a welcome opportunity to receive further guidance from the Board on design-patent-related issues. To date, however, only twenty-eight IPR petitions have involved a design patent. Fifteen IPRs have reached an institution decision—eight were instituted (meaning that the Board found there was a reasonable likelihood that the petitioner would prevail and the patent would be found invalid) and seven were denied institution (meaning that the Board found the petitioner did not carry its burden and the IPR does not proceed). Of the eight IPRs instituted, two are pending final written decisions and in six, the Board cancelled the subject patent. Cumulatively, there are thirteen opinions (seven denying institution and six finding a patent unpatentable) from the Board regarding design patents. Many of them contain helpful information for those prosecuting design patent applications. We will consider three of these decisions in detail.

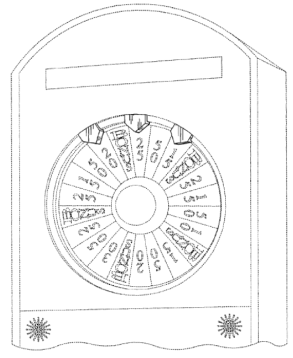

Vitro Packaging, LLC v. Saverglass, Inc., IPR2015-00947

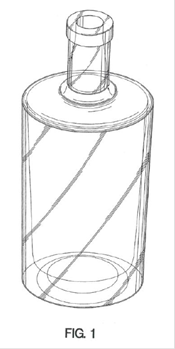

The design patent in this IPR was directed to the design of a bottle. The petitioner unsuccessfully challenged the validity of the patent on obviousness grounds based on two separate primary references in combination with other references.

|

|

|

U.S. Patent No. D526,197 |

Round Ink, 1906 |

CH No. 146 |

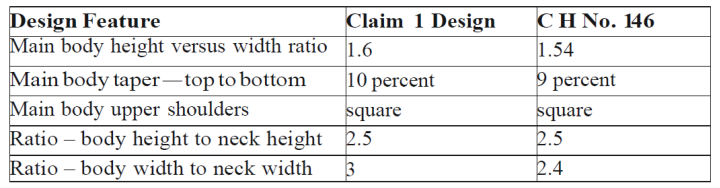

This decision is notable for three reasons. First, the petitioner proposed an exacting, numerical claim construction that included, among other things, specific height-to-width ratio (“approximately 1.6”) and description of the taper of the profile of the design (“approximately 10 percent”). In contrast, the Board adopted a lengthy prose description of each physical feature of the bottle design, without a single numerical calculation or comparison.

Second, through a comparison chart (shown below), the petitioner used its numerical-based claim construction in an attempt to establish that one of the references should be a primary reference because of its similar relative dimensions.

The Board rejected this type of comparison, in favor of a side-by-side visual comparison. As the Board put it, “[w]e are not persuaded by Petitioner, or its Declarant, that relative dimensions, at least in the case of a ubiquitous commercial product such as a bottle, are by themselves sufficient to evoke an accurate visual comparison between two bottles. We must look more closely at the distinctive visual appearances.....”8

Finally, the Board disagreed with the petitioner’s attempt to diminish certain differences as between the claimed design and the prior art as “less noticeable features,” and thus not barriers to a finding of obviousness. But, instead, the Board held that “just because a design feature is ‘slight’ does not by itself lead directly to the conclusion that such a feature would result in a de minimus difference in appearance.”9 As a result, the Board denied institution.

Premier Gem Corp. v. Wing Yee Gems & Jewellrey Ltd, IPR2016-00434

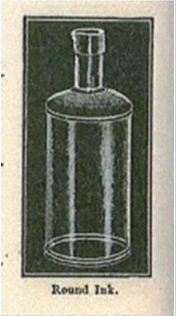

The subject of this IPR petition was a design patent for a diamond jewelry setting.

|

U.S. Patent No. D618,132 |

The petitioner relied on a single prior art design, the Lotus Caret design, as shown in multiple references, as its primary reference for its obviousness analysis, in combination with five secondary references.

The Board also denied institution in this case and, in doing so, set forth three important ideas. First, the Board challenged the quality of the disclosure in the secondary references, finding that “the details of the secondary reference designs are not clearly discernable based on the evidence in the record,” forcing the Board to “guess at what is shown in the photos of the secondary references” without supporting references.10

Second, the Board found that the petitioner improperly focused on “design concepts” rather than the overall visual appearance of the claimed design and the prior art. In sum, the Board stated that petitioner relied on “a general design concept that is too high a level of abstraction to be useful in the obviousness analysis.”11

Finally, the Board squarely challenged the petitioner’s obviousness analysis, concluding that “Petitioner appears to have selectively chosen certain design features of the secondary references (the mixing of stones of different cuts) while deliberately ignoring other design features of those references just so the claimed design would result. . . . This selective use of the design characteristics of the prior art suggests that it is driven by a hindsight reconstruction of the invention rather than the objective teachings of the references.”12

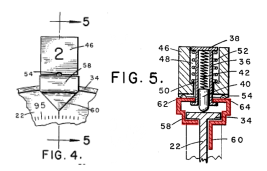

Aristocrat Technologies, Inc. v. IGT, IPR2016-00767

In this recent IPR institution decision, the Board denied institution on both anticipation and obviousness grounds. This IPR involves a design patent claiming a “gaming device having a display with multiple indicators,” with the pentagon-shaped arrows being the only elements of the claimed design (the remainder of the structures are in broken lines, and thus not claimed).

|

|

U.S. Patent No. D503,951 |

Corwin, US 3,203,391, |

The Board considered the petitioner’s anticipation argument using the ordinary observer test as set forth in International Seaway Trading Corp. v. Walgreens Corp.13 The petitioner argued that Corwin should anticipate the ’951 patent because the shape and proportion of Corwin’s indicators are “practically identical to the claimed design.”14 But, as the Board noted, the petitioner also admitted that the Corwin indicators “dip down at the ‘roof’ by bending toward the screen” (see red area in cross-sectional view shown above), but in petitioner’s view, the differences are “too minor to prevent a finding of anticipation.”15 The Board was not persuaded that the ordinary observer would find the “dip down” and other differences to be “minor, trivial, or insignificant differences” and declined to institute on this ground.16

Another important takeaway from this decision is that the Board noted the petitioner’s expert shaded only one surface of the pentagon shape, thereby “implicitly reducing the claimed design from three- to two-dimensions” and then proceeded to compare only this portion of the claimed design to the prior art.17 The Board held that the expert’s “failure to apply the art to the claimed design completely undermines his opinion regarding substantial similarity.”18

Lessons Learned

In each IPR institution decision described above, the Board maintained the validity of the design patent and did not institute the IPR proceedings. Accordingly, many of these holdings could be helpful in responding to an examiner’s office action rejecting a claim design on anticipation or obviousness grounds.

For example, the quality of the disclosure in the reference raised by the examiner might not be sufficient. Or, the examiner may appear to be applying a claim construction heavily based on numbers and measurements, ignoring the importance of the overall visual design. The examiner may only be comparing a single side of the claimed design to the claimed design and not considering the other views. The examiner may attempt to promote certain features and dismiss others as “less noticeable” or “trivial.” Or, the examiner may be selectively choosing certain design features in an obviousness combination that is the hallmark of impermissible hindsight analysis.

While the number of ex parte appeals in designs is low, the Board’s IPR decisions continue to be a good source of information about the Board’s interpretation of design law.

1 E.g., In re Cornwall, 230 F.2d 457 (CCPA 1956); Litton Sys., Inc. v. Whirlpool Corp., 728 F.2d 1423 (Fed. Cir. 1984).

2 Gorham Co. v. White, 81 U.S. (14 Wall.) 511 (1871).

3 Ex parte Asano, 201 USPQ 315, 317 (BPAI 1978); Ex parte Strijland, 26 USPQ2d 1259, 1263

(BPAI 1992).

4 Fiscal Year 2016, Patent Trial & Appeal Board, Receipts and Dispositions by Technology Centers, Ex Parte Appeals, http://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fy2016_aug_e.pdf.

5 To put this in perspective, in the last decade, design patents have typically represented between 7 and 13 percent of the total patents granted in the United States. U.S. Patent Statistics Chart - Calendar Years 1963-2015, http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/us_stat.htm

(last visited Sept. 19, 2016).

6 The file history of a design patent application is not publicly available until the design patent issues. If an application does not issue—such as if it was finally rejected and not appealed or if the issue fee is not paid—then the file history is not available to the public and neither is the appeal.

7 The notable exception would be those applications that are appealed to the Federal Circuit. See, e.g., In re Owens, 710 F.3d 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (affirming the Board’s rejection of the pending design patent application).

8 IPR2015-00947, Paper 13 at 14 (PTAB Sept. 29, 2015) (citation omitted).

9 Id. at 12.

10 IPR2016-00434, Paper 9 at 15 (PTAB July 5, 2016).

11 Id. at 16.

12 Id.

13 589 F.3d 1233, 1240 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

14 IPR2016-00767, Paper 8 at 10 (PTAB Spt. 14, 2016) (citation omitted).

15 Id.

16 Id. at 12.

17 Id. at 11.

18 Id. at 12.